THOUGHTS, DREAMS & ACTION

If we’re going to get through the next few years, we need a change of narrative so profound that our entire culture changes direction. We need not just new stories, but a whole new shape to what a story is. And it will start with our writing.

THOUGHTS | DREAMS | ACTION

If we’re going to get through the next few years, we need a change of narrative so profound that our entire culture changes direction. We need not just new stories, but a whole new shape to what a story is. And it will start with our writing.

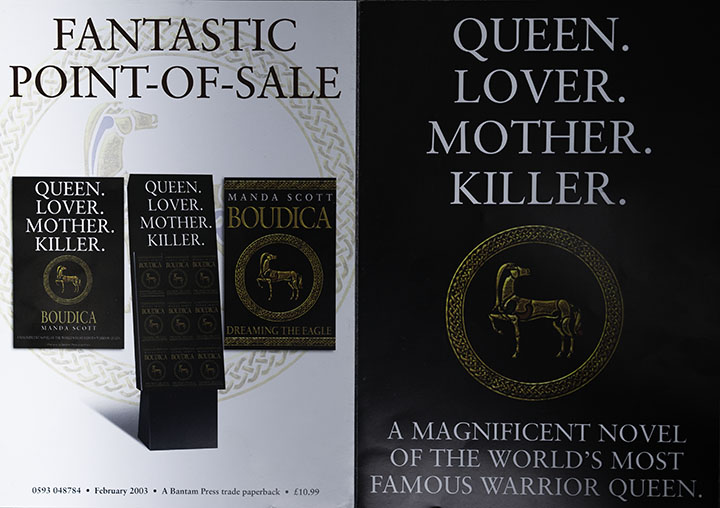

Boudica: 15 years on

June 2015 marked fifteen years since Dreaming the Eagle was first published. There were no electronic versions then, no Facebook, no Twitter. Email was on dial up, and we waited until midnight to dial in because the lines were engaged during the day.

I had a career as a thriller writer, but the Boudica books were sitting there, in the back of my mind, waiting to be written. I’d read Rosemary Sutcliff’s Eagle of the Ninth as a child, around the time my Dad took my brother and I to visit the Brochs at Glenelg in Scotland. At nine years old, I’d walked among the stones and got my first taste of the things Sutcliff wrote about: the Seal people, the priests of the Horned Moon god, the mysteries behind the goat-skin door that we never got to see in her world of Roman senators and straight roads and the honour of the Eagle. I read everything she wrote, but she never really lifted the goat-skin flap: the mysteries remained mysterious, the rites and the rituals were hinted at, but never shown. At the Brochs, the fictional world became real – I still didn’t understand the patterns beneath the surface, but I knew that I wanted to.

Sutcliff did introduce me to Mithras though, which was my first foray into a world beyond the Protestant churchianity of the small Scottish village in which I grew up. Soon after, I read The Last of the Mohicans, which opened the door wider into other worlds and other ways of living and was enough to set the path for the rest of my life.

Being Scottish to the core, I spent my teenage years exploring the druids, what they thought, how they practiced: not much was known, which meant that it was easy to find it all. Later, as a veterinary student in Glasgow, I found a local (ish) group who practiced the things I’d been reading about. We spent weekends exploring the caves near Edinburgh’s Roslyn chapel (the one that Dan Brown later made famous in his Da Vinci Code) and reading old texts. When I outgrew their particular brand of Keltic/Kabbalah mysticism (incorrect spelling deliberate), I borrowed a tent and went camping out in the Highlands for long weekend on my own, trying to find the ways to connect with the old gods that our ancestors must have known and that I was convinced were still there if only I could find the key.

It was natural, then, when I’d served my writing apprenticeship with the thrillers, that Boudica was hovering on the borders of my unconscious, waiting for the life of the page.

Why I wrote the Boudica Series

Of all the reasons there are to write, the process of discovery is one of the most compelling. We write the things we want to know because in the writing, in the getting-under-the-skin of our characters, their time and place, our own worlds open up.

In writing the four Boudica: Dreaming books, therefore, I was writing for myself, to open the doors that Sutcliff had kept so resolutely shut, to bring the dreaming to life, to find who we were before the Romans came, so that I, at least, might know who I could be if I ever managed to shed all the cultural trappings they left us.

I was writing to find what felt authentic to me, to take my own practice deeper while creating books that I thought might touch one or two people and let them see the world differently. I didn’t hope for that – you learn early in a writing life that the book you write and the book people read are very often entirely different. It was always possible that the entire reading world might have read them as historical thrillers and carried on as before, untouched by anything deeper.

We’ve sold somewhere around a million books since then. These things are interesting in the world of book promotion, but what I wasn’t expecting is the resurgence of interest – or the rash of tweets, Facebook posts, DMs emails and website sign-ups from America, Canada, New Zealand, Finland, Germany, Ireland, and all parts of the UK, from people whose lives have changed, who have been touched by the dreaming, who have found that sense of coming home to something so old, so primal, so much a part of our inheritance that once we reach it, we can’t imagine how we ever left.

And so we find that the books have touched people lives in the way that mine was touched by Sutcliff, Stewart, Renault and all the other life-changing authors of my youth.

For a writer, there is no greater honour. In the days when writing seems more like mining granite with a cardboard teaspoon, this is what makes it worthwhile. Thank you all.